London's Auxiliary Ambulance Station 50

In recent years histories of the Second World War have increasingly acknowledged the millions of South Asian troops who served as part of the Allied forces in Europe, Africa and Asia. Closer to home, however, the contributions of London’s South Asian communities to the civil defence of the capital remain overlooked and neglected. Here we draw attention to some of these untold stories by examining a lesser-known aspect of the London County Council’s Auxiliary Ambulance Service.

Indian troops

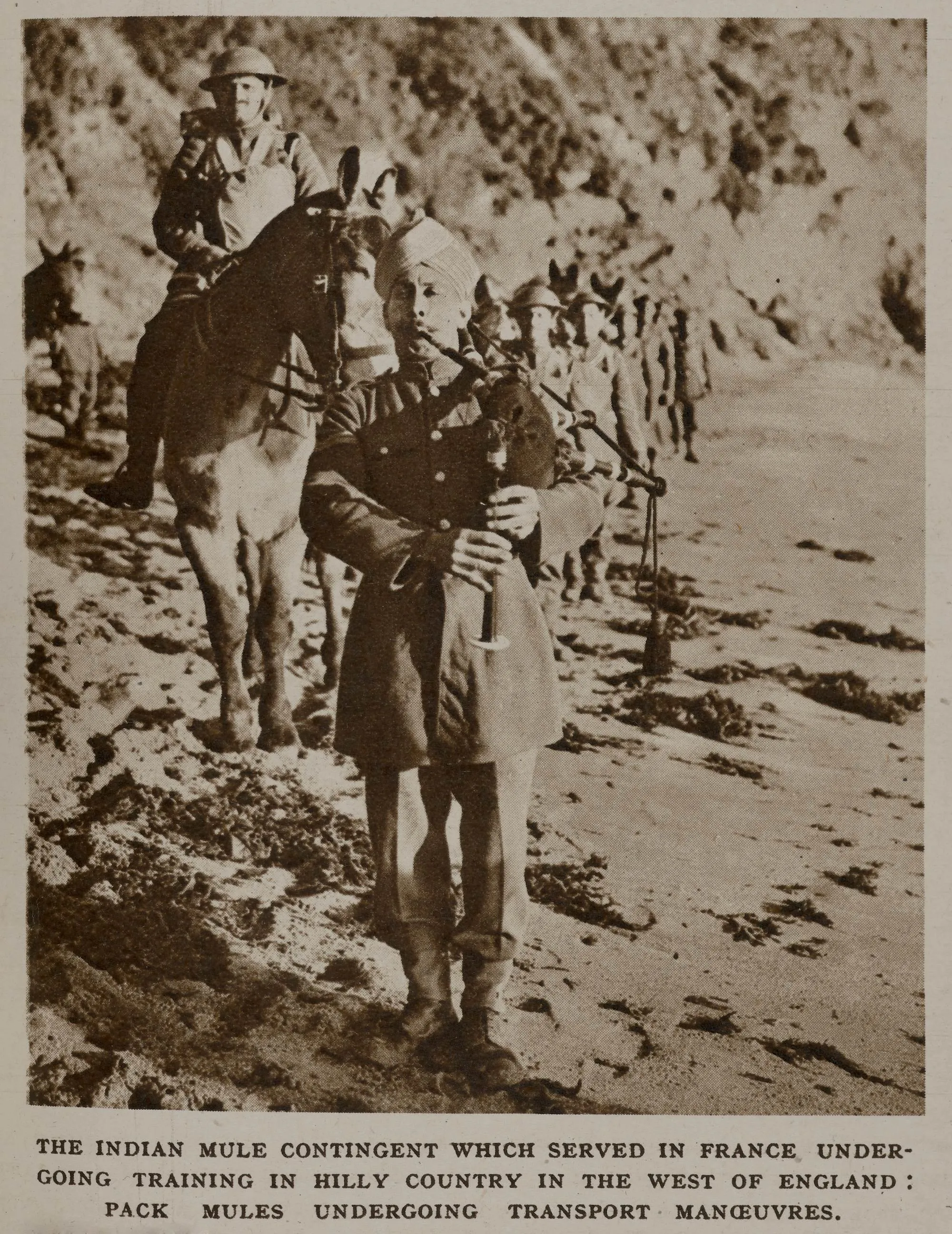

The sight of Indian troops on the streets of London during the war would not have been unusual. Indian military personnel were based in the United Kingdom throughout the conflict. For example, 24 Indian Air Force pilots were sent to Britain in September 1940 to fly with the Royal Air Force and Indian Mule contingents were stationed in Derbyshire, Cornwall and Wiltshire after having been evacuated at Dunkirk. Their presence was widely reported in the press as war propaganda.

The Indian Comforts Fund was set up by South Asian and British women to provide for these troops, as well as for Indian prisoners of war in Europe and merchant seamen stranded by disruptions to sea routes. One aspect of the Fund’s work was to organise recreational events which included regular visits to London. One such visit took place in October 1940 when troops were invited to tea with the Lord Mayor at Mansion House.

London and South Asia

Indian soldiers were but a small fraction of the many South Asians resident in London in the 1930s and 1940s. The capital’s links with South Asia (broadly the regions known today as India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka and Nepal) were many centuries old and the 1939 census shows that on the eve of war there were significant South Asian civilian populations, some transient, others of long standing.

The census also indicates that many of the people listed were already engaged in Civil Defence work when war broke out. Their stories should be integral to our understandings of the ‘spirit of the blitz’ and histories of the Home Front. Yet, the popular memorialisation of the Second World War consistently excludes these contributions and those of the many other diverse communities resident in the capital, even though evidence for them appears throughout the archives.

London Auxiliary Ambulance Service

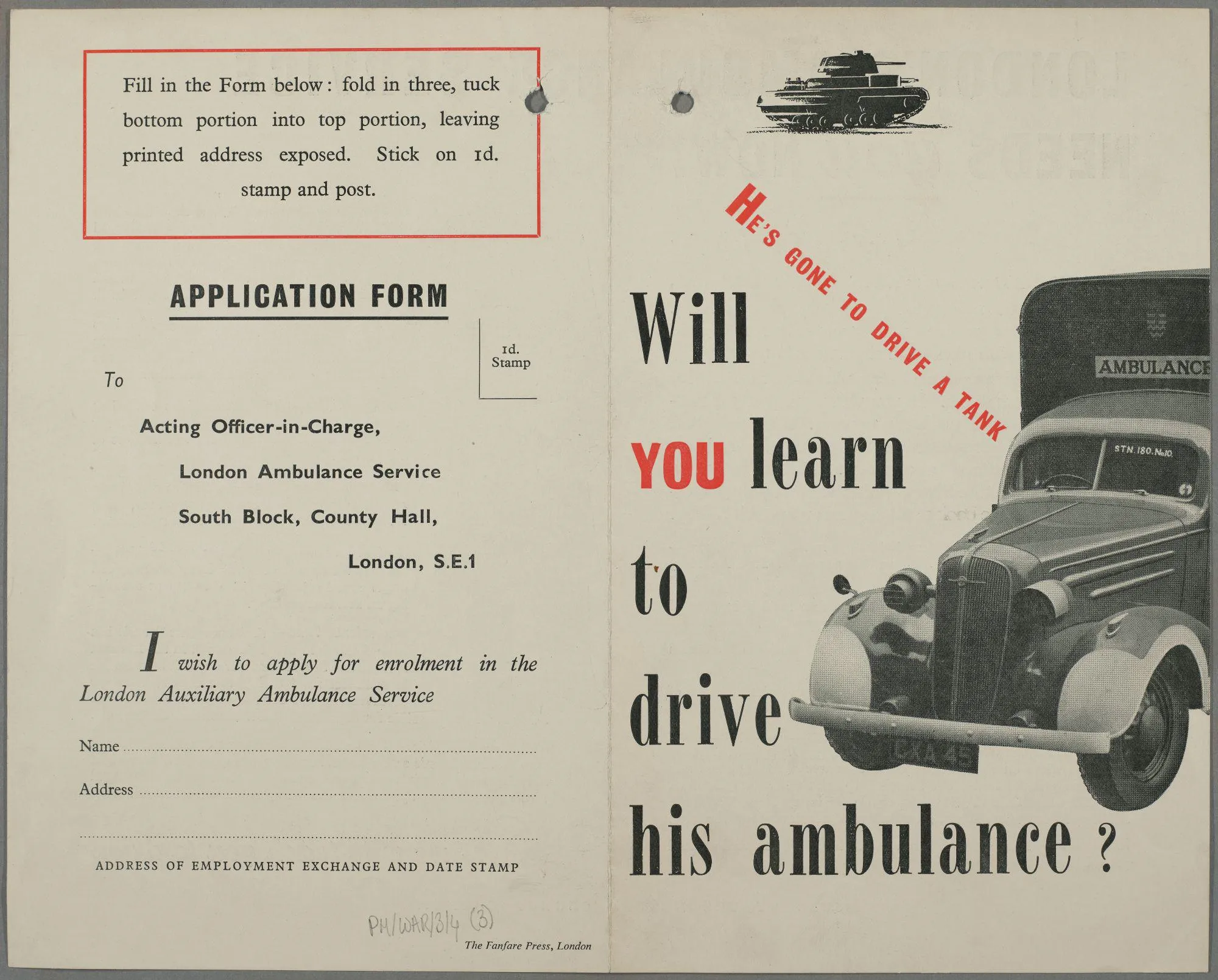

The London Auxiliary Ambulance Service (LAAS) was created by the London County Council (LCC) to support the regular ambulance service in its treatment of air raid casualties. Throughout the war, the LCC ran recruitment campaigns to encourage Londoners to volunteer for this civil defence work.

These recruitment campaigns often focused on women. Promotional leaflets such as the example shown above list incentives to join (volunteers were to be trained in driving skills, car maintenance and first aid) and they often use language which is predictably gendered and arguably patronising. Women would later complain that their jobs and working conditions were often less favourable than those of male colleagues. Nevertheless, thousands of women responded and listings for Auxiliary Station Officers (ASO) in 1939 show that well over half were women.

Auxiliary Ambulance Station 50

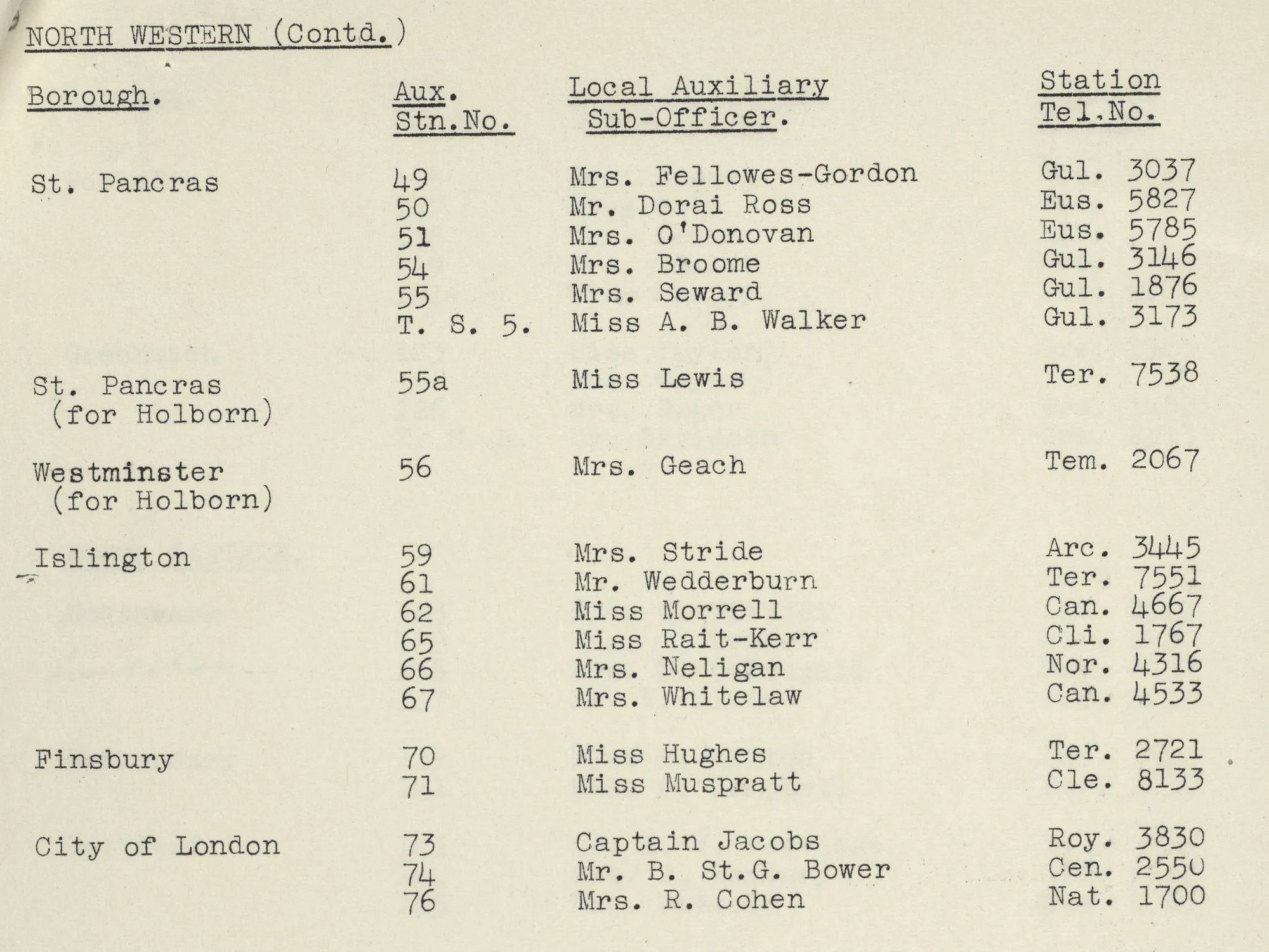

On 12 September 1939 Auxiliary Ambulance Station 50 was established by the LCC at Nash Street in St Pancras. Its first ASO was Dorai Ross (you can see his name listed in the image above). Born in Tranquebar (now Tharangambadi, Tamil Nadu, India), Ross was living in Gower Street at the outbreak of war with his wife, Rosemary who was originally from Madras (Chennai).

He convinced the LCC to set up an ‘Indian’ station by recruiting London’s South Asian populations as ambulance attendants and drivers. Over a hundred people responded, including nine women. The majority of the station’s workers were of South Asian heritage but there were white British, South African, Burmese and Caribbean volunteers at the station too. There appear to have been about 125 people working there by 1940.

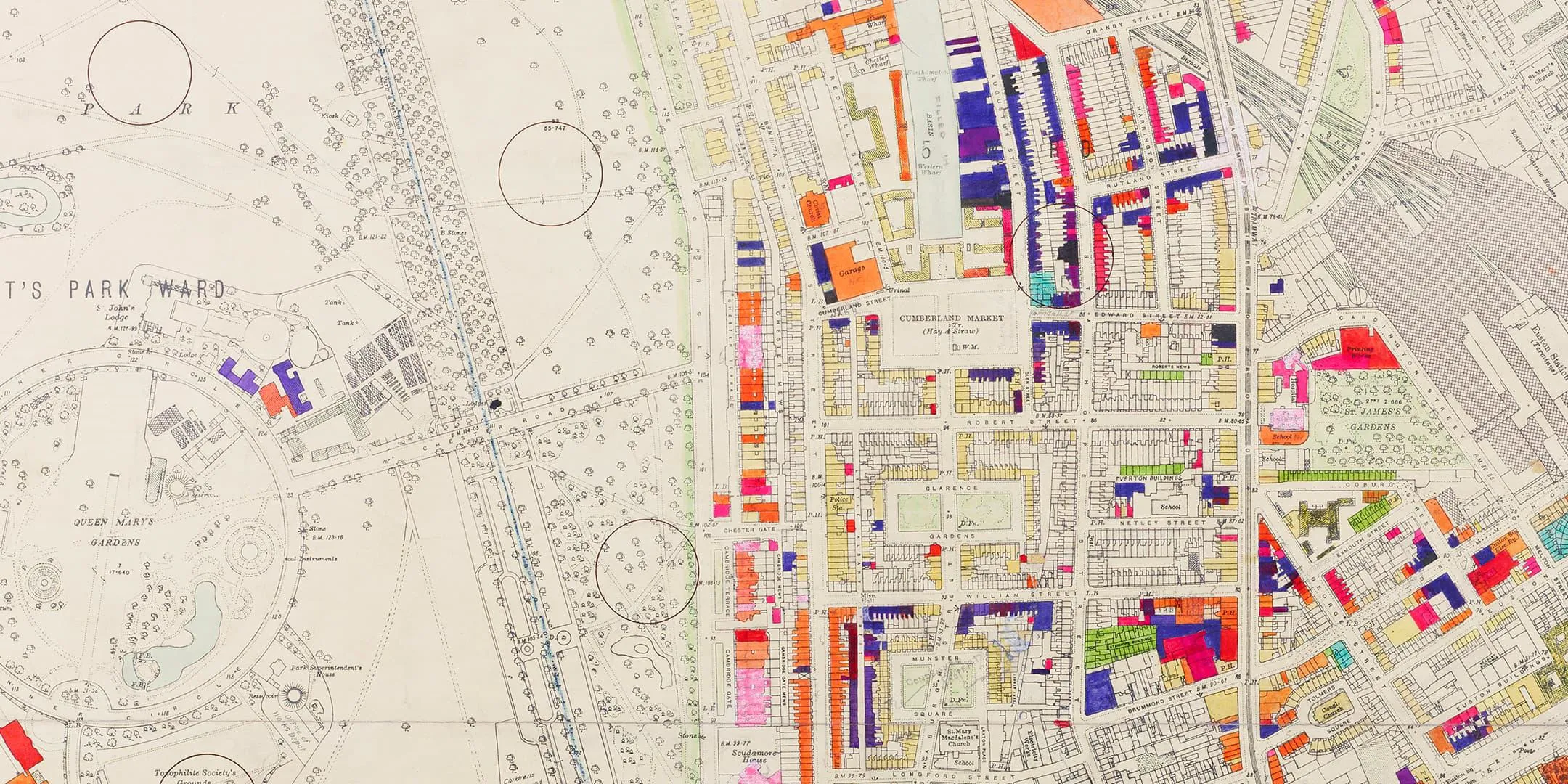

Station 50 was initially based at Nash Concessionaires Limited, Nash Street, St Pancras. It subsequently moved to Pass and Joyce Ltd car agents at 21 Augustus Street but was forced to move once again to new premises at 20 William Road after the building was irreparably damaged by an air raid attack on 25 September 1940. Evidence suggests that the premises were far from comfortable. A survey of the William Road building in 1942 describes it as inadequate and inconvenient.

Pictorial evidence of South Asian civil defence volunteers can be hard to find in the archive collections at TLA, but two images have been identified. A photograph published in the Illustrated London News on 23 September 1939 shows the first cohort of South Asian recruits to the LAAS.

New recruits to LAAS Station 50

None of the people are named, but Dorai Ross and his wife Rosemary are likely to be there, given their close involvement. The Imperial War Museum has a propaganda poster showing two South Asian women ambulance volunteers from Station 50. Once again, neither woman is named but we might assume that one is Rosemary Ross.

The second image shows the Queen inspecting LAAS staff at County Hall on 6 May 1941. On the right, South Asian staff wait to be introduced. Although possibly from Station 50, records show that South Asians in fact worked at stations across London, so we cannot be sure of the link to St Pancras.

The London County Council Archive

That said, we are able to find more information about many of the people who worked at Station 50 because of an extraordinary document in the archive of the LCC. This is a file resulting from a tribunal held to examine complaints about irregularities and indiscipline at the station in 1940 (LCC/PH/WAR/003/060).

The file is not just a window into the workings of Station 50 in the early months of the war, it introduces us to 50 or so volunteers who are called to give evidence. Their verbatim responses to the questions put to them by council officials are recorded word for word in the transcript on file. They allow us to ‘hear’ individuals ‘speak’ and give us details so often missing from other records.

The file is full of drama and includes many revelations about the lives of the volunteers. We learn about their relationships and networks, rivalries and tensions, employment and political views. Collectively, the file is evidence of the diversity within South Asian communities living in London during this period. We encounter doctors, nurses, actors, sailors, boxers, restaurant managers, barristers, waiters, businessmen, shop owners, journalists, students, sons of Rajahs and even spies!

A History of Colonialism

But the file is not just a record of the individuals who appear, it also throws light on the history of colonialism. Although the tribunal is concerned with investigating Dorai Ross as ASO, the LCC officials are quick to link the issues at hand to the broader situation in British India.

There are anxious questions around the extent of anti-colonial feeling amongst the South Asian staff. At the time, the British government actively promoted the ambulance station as propaganda to show the ‘loyalty’ of the Empire. Such involvement in the war effort was a convenient counter narrative to the mass anti-colonial movements which the government was violently suppressing in India.

Ironically Dorai Ross, the man they are investigating, is the very epitome of this pro-British propaganda and repeatedly voices his loyalty to the Empire. But the authorities are clearly nervous about the situation at the station. We learn that the police have recruited a spy to report on pro Independence feeling, perceived communist activity and general anti-British sentiment.

Their concern is not unfounded. Many of the volunteers who address the tribunal voice clear opposition to empire and call out the racism they experience at the station from their white colleagues (which they think Ross is complicit in encouraging).

Interestingly, we discover that Udham Singh, an anti-colonial revolutionary, passes through Station 50 in its early months. Singh went on to assassinate Michael O’Dwyer, former Governor of Punjab at Caxton Hall on 13 March 1940. At his trial he said the act was in revenge for O’Dwyer’s role in the 1919 massacre at Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar when troops had fired upon an unarmed crowd protesting British rule, killing several hundred people.

But the situation at Station 50 is more complex and nuanced. Despite public calls by the Congress Party in India for Indians to refrain from helping the war effort, it is clear that for many of the tribunal witnesses, civil defence work in support of fellow Londoners was not incompatible with a commitment to fighting for India’s independence.

Racist stereotypes

This introduces dynamics and ambiguities which are missing from more simplistic popular narratives which presents the war as 'good v evil'. We get a sense that individuals are wrestling with their consciences. Simultaneously accepting the very real risks involved saving casualties on the streets of London, whilst knowing that the freedoms Britain claimed to be fighting to preserve in Europe were actively being denied and repressed in India.

A central question which obsesses the LCC officials becomes a metaphor for Empire: whether an Indian can or indeed should be in charge of the station. Racist stereotypes question the suitability of South Asians for leadership. Witnesses are also repeatedly asked if they think preoccupations with caste and religious belief are an impediment to the successful operation of the station (a resounding ‘no’ from the majority of the volunteers).

Such questioning encapsulates the classic paternalistic defence of colonialism, repeatedly used to justify Britain’s denial of self-rule to Indians and its unrelenting suppression of anti-colonial struggles. Although the tribunal file does not give a final ruling on Dorai Ross, we discover from later records that he is in fact replaced as ASO by Samuel Macfarlane, a former colonial official who has served in India and who (presumably in the eyes of the LCC officials) has experience of ‘dealing’ with Indians.

The appointment represents a ‘return to empire’ of sorts, but we are reminded that the war will bring change. In India a mass ‘Quit India’ campaign is building, tensions are mounting and Independence via the violent traumas of Partition beckons.

Conclusion

The more we think we know about history, the more there is to discover. The Second World War is perhaps one of the most widely considered topics in British history but the way it is memorialised in popular narratives is often narrowly framed.

The ‘Spirit of the Blitz’ is synonymous with the idea of communities coming together in times of adversity. In 1940s London those communities were diverse and multilayered. The fact that South Asians were amongst the many thousands of Londoners who took on civil defence duties should come as no surprise and yet these stories remain relatively unknown.

Such omissions narrow our understanding of London’s past. The history of Station 50 encourages us to think beyond the popular historical narratives to examine the multilayered nature of London’s response to war. What we find is invariably more complex, challenging and interesting.

London in the Second World War exhibition