Revisiting the Cooper Family collection

Exploring omissions, language and content in our catalogue descriptions

When a user contacted us about unexpected content in one of the records in the Cooper family papers (ACC/0775), it spurred members of our Terminology Working Group to re-evaluate the catalogue descriptions for the whole collection. Here we discuss what we found and how this work is crucial, not just in removing harmful language from our catalogues and flagging harmful content, but more widely in opening up neglected histories and making important connections to Britain’s colonial past by improving catalogue descriptions.

Identifying the problem

Where ignorance is bliss, 'Tis folly to be wise

Such sentiment is the antithesis of the inclusive cataloguing and decolonising work undertaken by our Terminology Working Group whose members work to identify and remove (or at least contextualise) harmful language which appears in the catalogues at The London Archives (TLA).

What is Inclusive Terminology?Identifying insensitive language in the millions of entries on our catalogue is a challenging and lengthy task. Progress can be slow because each instance of a word needs to be researched meticulously for meaning and context before any changes can be made.

Inevitably, there are times when we’d rather not think about it, but ignorance is most certainly not bliss in respect to this work. Doing nothing perpetuates the use of harmful terms, which in turn potentially frames groups of people or cultures negatively and reinforces the marginalization of particular histories. So, TLA is committed to undertaking this work.

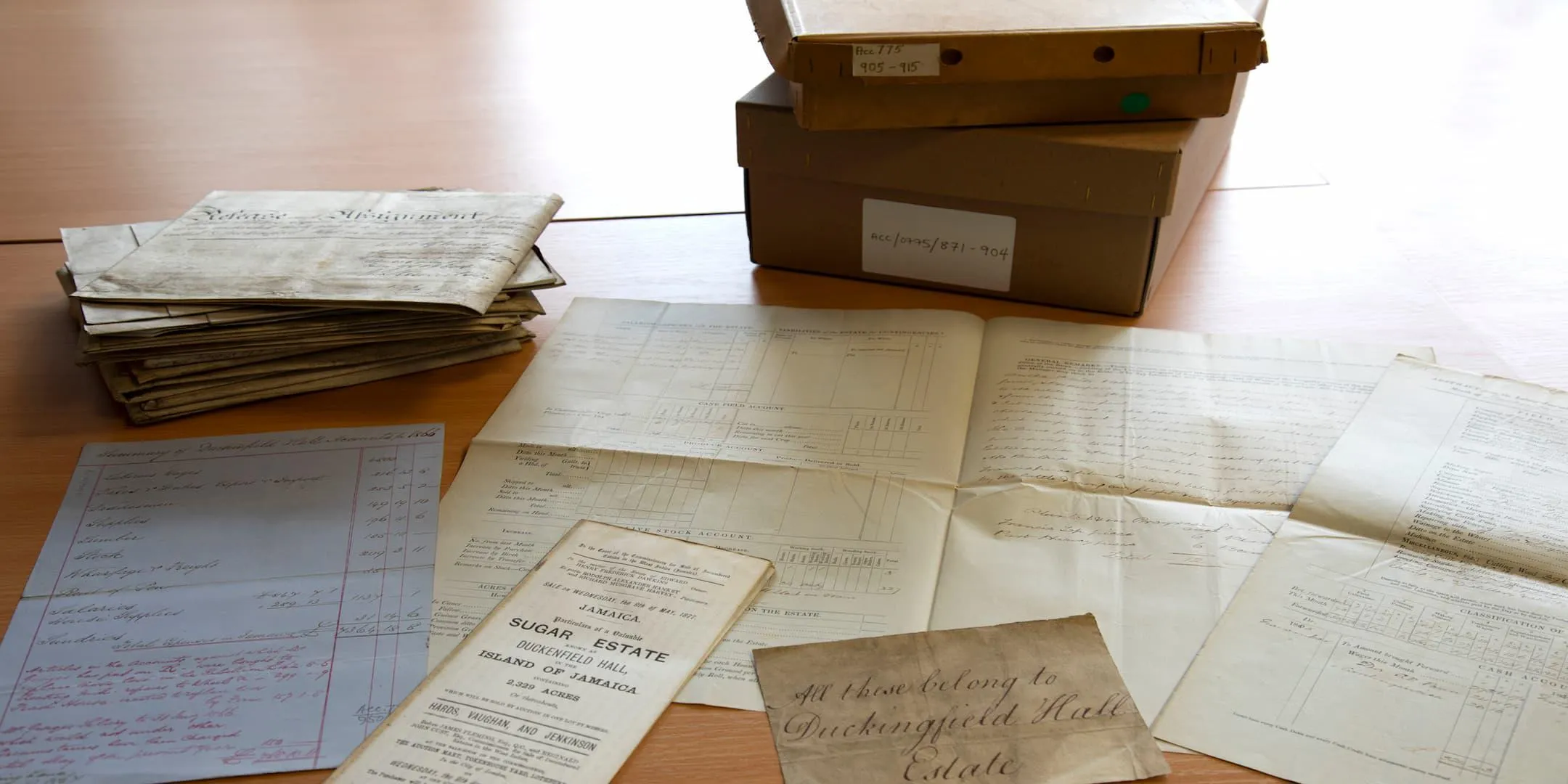

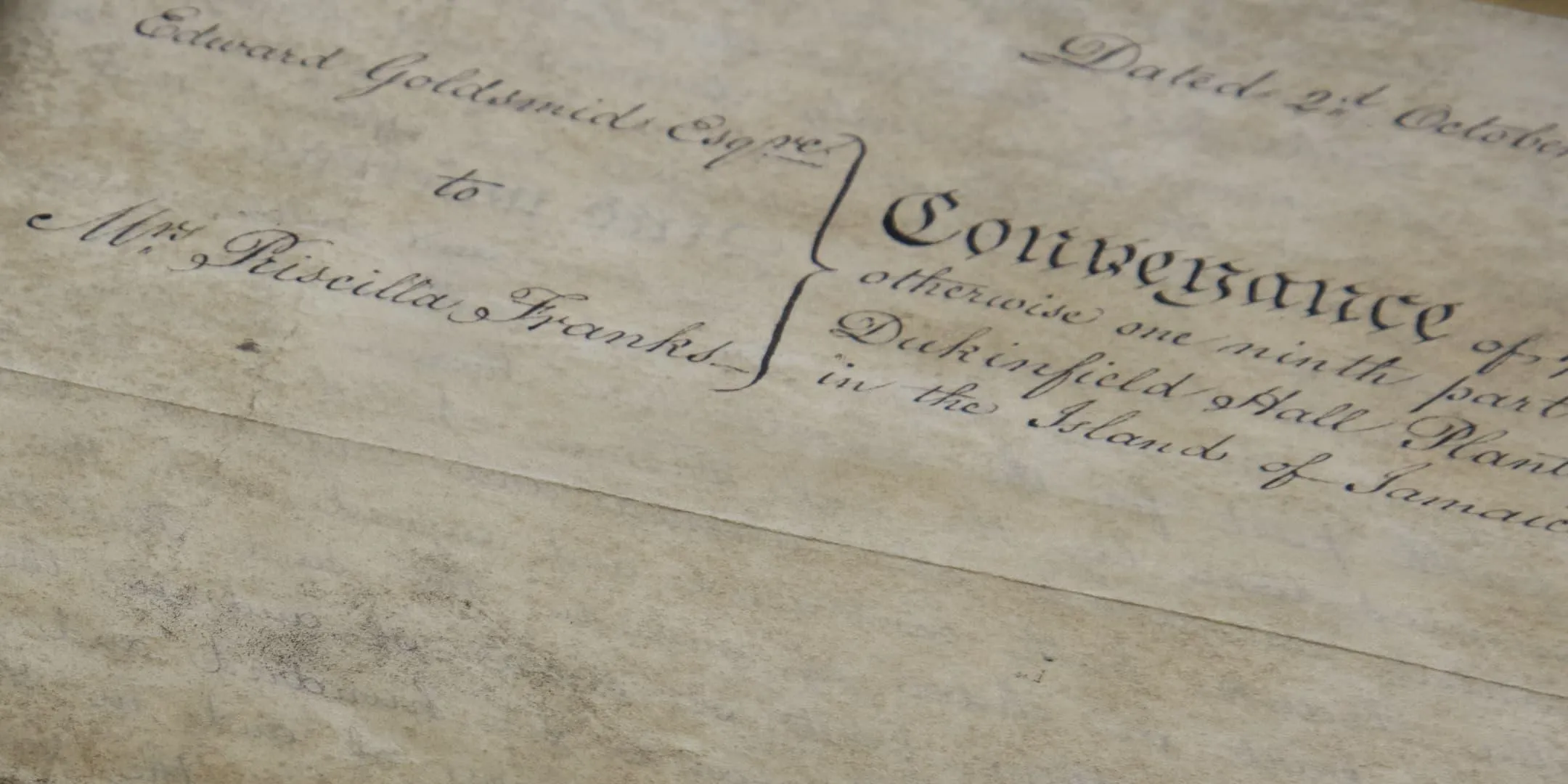

As part of this project, back in December 2023, group members surveyed the catalogue for the Cooper collection (ACC/0775) to identify the harmful language used in some of the catalogue descriptions. The Cooper collection is one of the many family and estates collections we care for, and it consists of papers belonging to Lady Cooper, her children and grandchildren. Lady Cooper (1769–1855) was born Isabella Ball Franks, and she inherited a considerable amount of money from her family, along with properties in Isleworth and sugar plantations in Jamaica and Grenada.

Our terminology work resulted in changes to 25 entries on the catalogue, mainly to replace repeated use of two unacceptable terms relating to enslavement. But when one of our users contacted us in January 2025 to tell us about what they had found within a document in the very same collection, we decided to revisit this work.

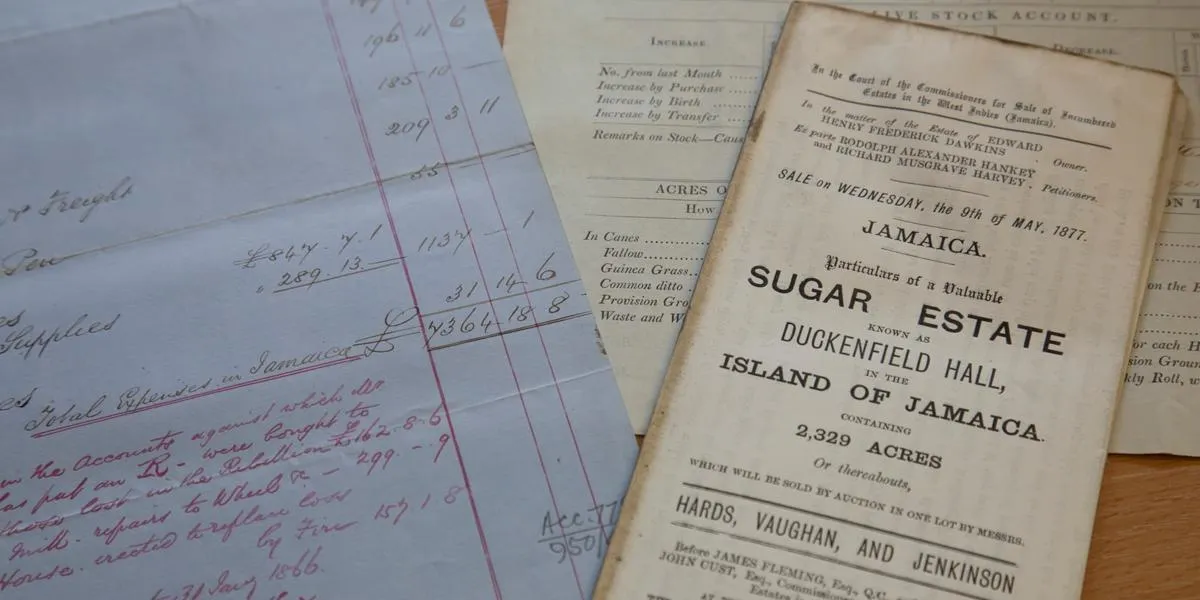

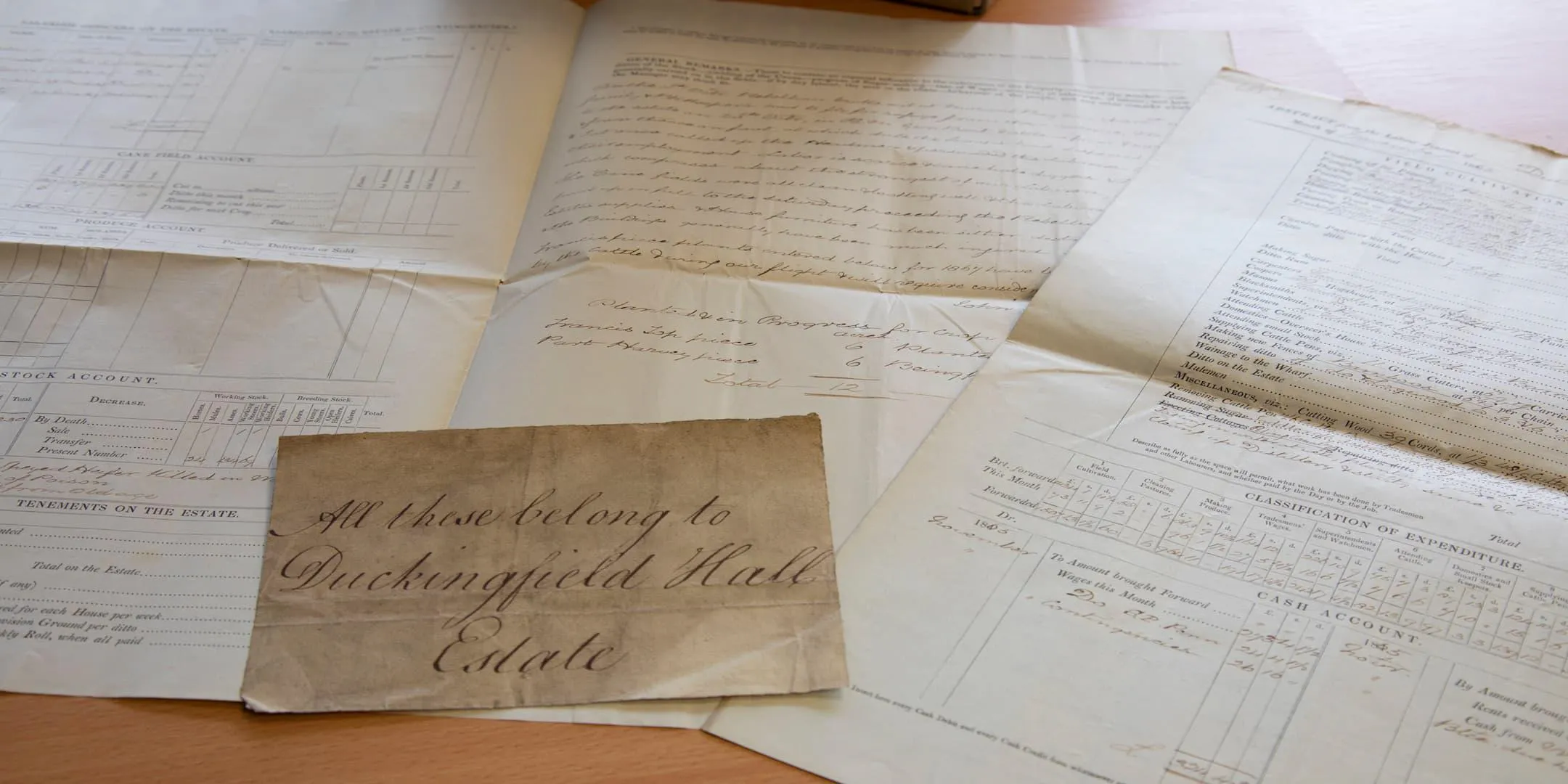

The user had consulted ACC/0775/855 and informed us that the description (‘Abstract of title no. 4 to one third part of a Plantation and Estate called Dukinfield Hall in the Island of Jamaica’) made no mention of the fact that the document included explicit reference to the enslavement of Black people, used unacceptable language throughout and, most notably, included a list naming the enslaved people forced to work on the estate.

This revelation was a cause for concern on a number of levels: firstly, the catalogue gave no forewarning to the user that they would encounter explicit reference to enslavement contained in this document; secondly, it meant important information about the record had been omitted and was not available to potential researchers searching our catalogues; and finally, because this collection had been addressed as far as our Terminology Group work was concerned, it exposed an obvious limitation in our methodology: that just focusing on the visibility of harmful language on the catalogue alone will not identify all harmful language and content within the documents themselves.

So, we decided to use the collection as a test case to see how widespread the problem might be. We identified all the records which according to the catalogue related to estates in Jamaica and Grenada and consulted each document in turn to assess content. Out of 456 documents checked, we discovered that the overwhelming majority in fact contained explicit reference to the enslaved people forced to work on the estates. Yet only a tiny fraction of their catalogue descriptions referred to this fact. The situation prompted us think about why this might be, how it might affect the way users interact with the collection and how we could improve the catalogue descriptions.

Why might this be the case?

The original catalogue descriptions to the collection were created a long time ago in 1960s. The harmful language probably appeared in the descriptions because the cataloguer replicated words found in the original documents and/or chose to use words in common usage at the time the catalogue description was written, but which would not be used today.

But we can only guess as to why so many of the explicit links to enslavement were omitted. The cataloguing archivist might have considered the centrality of enslavement to 18th and 19th century sugar estates of Jamaica to be so widely known as to make further prompting unnecessary. But this is probably wishful thinking. In fact, the tone of the original administrative history for the collection suggests quite the opposite: a tendency here to underplay the impact of enslavement on the fortunes of the family.

For example, the original text concentrated on the family tree and the lines of inheritance for the various properties, both in the UK and the Caribbean. It acknowledged that Lady Isabella Cooper inherited sugar plantations via her aunt Priscilla Franks and there was passing reference to the fact that records include lists of enslaved people. But the text was also at pains to point out that the family did not directly profit from this enslaved labour because slavery had been abolished shortly after Isabella inherited the properties.

The logic of the statement might appear sound, but it is unsubstantiated and in fact contrary to the evidence. For one thing, it fails to acknowledge that Isabella claimed and received substantial compensation from the ‘Commissioners of Slave Compensation’ after abolition in 1834. And importantly, given that a third share of the plantation in Jamaica (along with shares in plantations in Grenada) had been held by family members since 1770s, it also inexplicably ignores the fact that this must have contributed significantly to the family’s collective (and considerable) wealth over many decades.

The inclusion of this statement is a clue to understanding the wider omissions. It suggests a defensiveness not uncommon in discussions about Britain’s involvement in the transatlantic trade in enslaved Africans. A necessary ‘disclaimer’ to accompany the muted acknowledgement of the family’s exploitation of enslaved labour. Combined with the omissions in the individual document descriptions, the effect is to simultaneously both normalise and render invisible the centrality of enslavement both to the family’s fortunes and more generally to Britain’s development.

Why do these silences matter today?

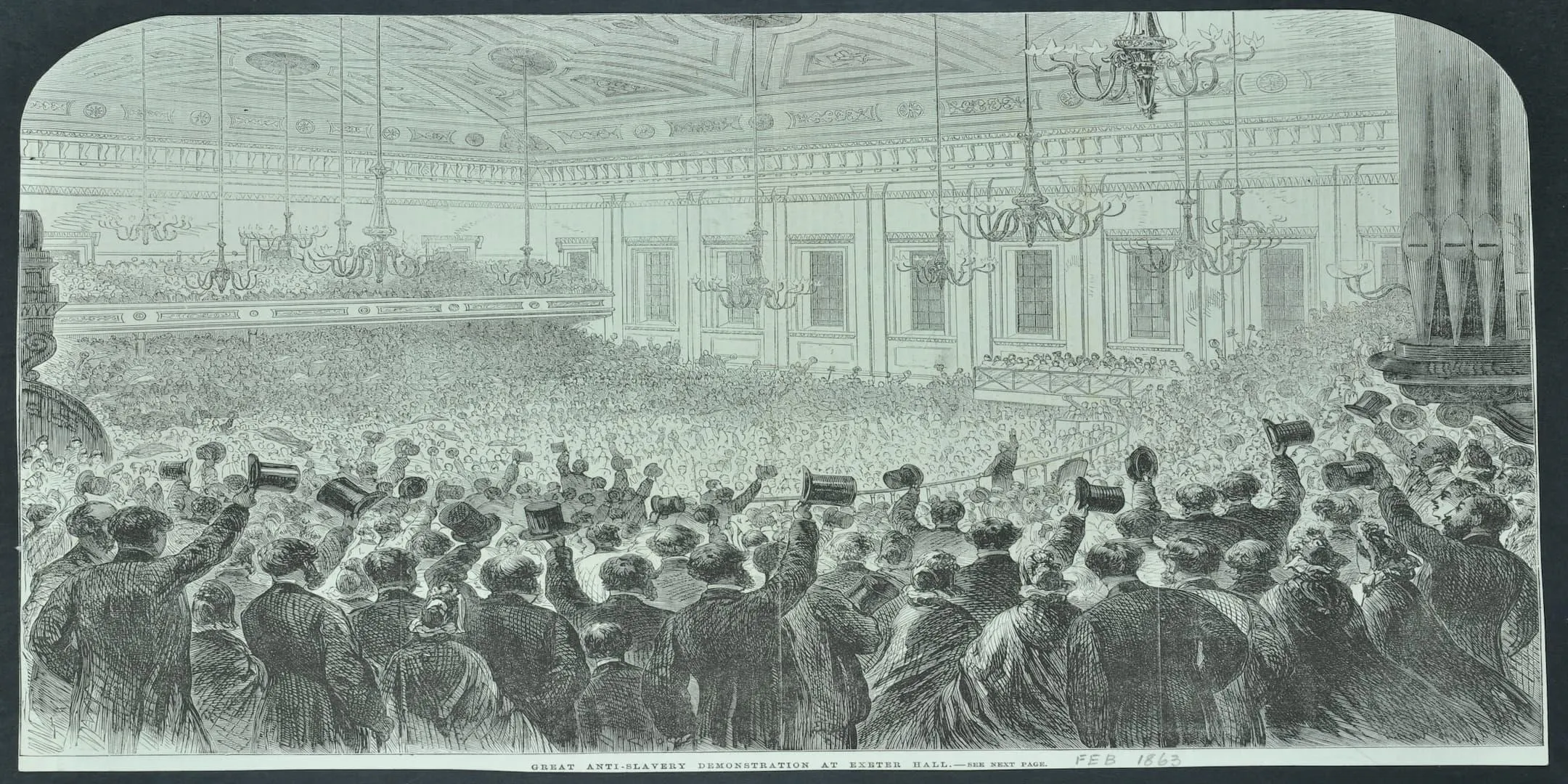

These silences matter because they enable a collective amnesia about important aspects of British history. A survey by the Repair Campaign published in March 2025 which asked people in Britain about their knowledge of the history of slavery confirmed that most people are ignorant of the scale and legacy of Britain’s involvement in enslavement and colonialism.

This is important because we cannot understand the development of London or Britain without acknowledging these histories. Over the centuries, the diversity of its populations, the grandeur of its buildings, the wealth and power of its institutions and businesses, the richness of its cultures and even the availability of daily commodities were all intimately linked to enslavement and colonialism.

But this is not just an academic exercise. It is as much a question of injustice as one of historical inaccuracy. That the people enslaved and/or colonised by Britain are so often written out of mainstream historical narratives is itself a legacy of colonialism and a product of the racism which underpinned it. A failure to challenge these omissions results in peoples, communities and cultures being marginalised, misrepresented and devalued which perpetuates narratives rooted in racism. And the legacies of colonialism persist today. Understanding and addressing contemporary racisms and inequalities requires engagement with these histories.

What can TLA do?

The way TLA presents the collections in its care defines what makes the mainstream narratives of British history and what does not. Omissions from our catalogues actively contribute to a collective amnesia by underplaying and/or neglecting important aspects of Britain’s past. It is therefore essential that we revisit our catalogues to identify major omissions and improve the descriptions of the records. This is a crucial strand of our wider decolonising work.

For the Cooper collection, it means ensuring that catalogue descriptions to all the documents which predate the abolition of slavery in 1834, and which relate to the Jamaican and Grenadian plantations make clear the fact that those estates were dependent upon the labour of enslaved people. This is irrespective of whether individual documents include explicit reference to that labour. Omitting to make these links is an act of silencing and decontextualises the information recorded.

What have we done?

We have now added content warnings to all the records containing reference to enslavement and have provided additional information in the administrative histories and scope notes to better acknowledge that sugar plantations depended upon the enslavement of Black people and the exploitation of their labour. Where changes have been made, you will see the following phrase in the content note field:

This catalogue entry was updated as part of TLA's ongoing Inclusive Terminology Review to examine and remediate offensive or harmful language in cataloguing and archival description. The catalogue has been edited to better acknowledge the ownership of plantations and enslavement of Black people

Titles and/or scope notes have been rewritten to identify content which relates specifically to enslaved people on the estates. We have also been able to expand many of the descriptions to better reflect the material contained in the collection. This process of catalogue enhancement has identified a wealth of information and a few noteworthy references.

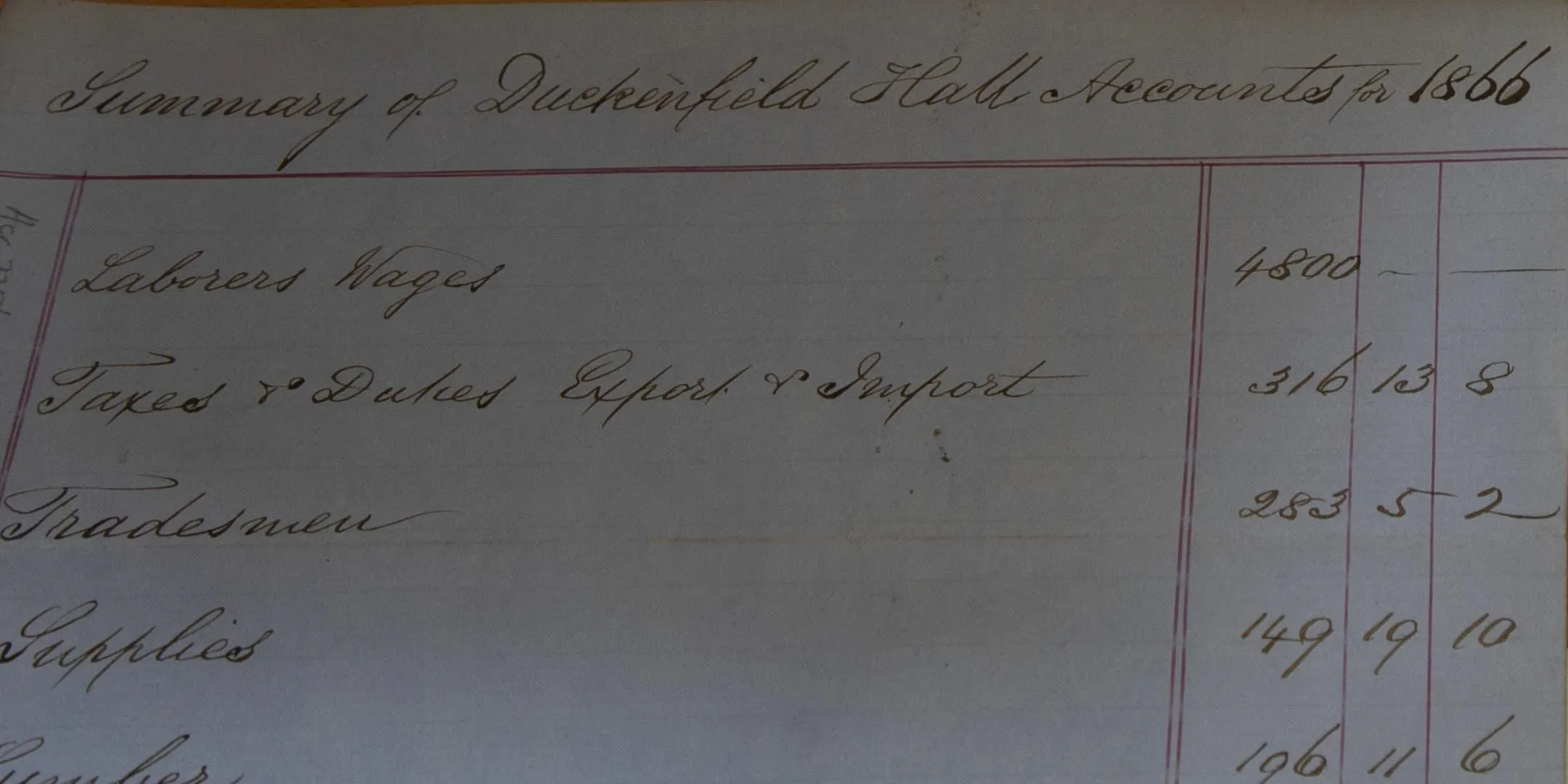

Research potential

Of particular interest is what the records tell us about the management of the Dukinfield Hall estates in Jamaica after the abolition of slavery in 1834. Letters and work journals document the transition from the exploitation of enslaved labour to a system of wage-based labour (ACC/0775/928, 929, 949 & 950). Estate managers are clearly concerned with the resulting reduction in the profitability of the estate. For example, a letter written by an agent to the Dowager Lady Cooper in 1842 laments that “the present mode of cultivating estates by free labour has proved a much more expensive one than under the former system of slavery” (ACC/0775/954/2).

Letters from the 1840s and 1860s consistently refer to difficulties finding Jamaicans willing to work on the estates. A letter from June 1842 complains that abolition has resulted in a shortage of labour on the Island and goes on to state that 40 Africans have been recently ‘imported’ to work on the estate (ACC/0775/929/4). This is a reference to the system of indentured labour which plantation owners in Jamaica increasingly relied upon as a steady source of labour after the abolition of slavery in 1834.

Letters from the early 1860s include multiple references to indentured workers from Africa (we’re never told precisely where in Africa), as well as indentured workers from other territories of the empire including India and China (ACC/0775/949/57, 58, 83 & 85; ACC/0775/950/9, 12, 17 &21). One letter from 1862 describes the arrival of a ship from Africa bringing 390 “fine healthy young people”, some as young as 12 years of age (ACC/0775/929/16G). Only the date of the letter (and possibly also some changes in the descriptive language used) assure us that slavery has been abolished.

There are also a number of references to important historical events. Letters from the early 1860s mention the Great Revival, a religious movement combining elements of Christianity with African religious beliefs which emerged in Jamaica in 1861. Ever mindful of efficiencies, the estate managers complain that greater preoccupation with religion is keeping labourers from working on the estate (ACC/0775/949/78).

Most interestingly there are references to the Morant Bay Rebellion. This was an uprising led by Paul Bogle in October 1865 in protest to the injustices and poor living conditions faced by many Black Jamaicans on the island (ACC/0775/950/43–50). A work journal states:

On 11 October Rebellion broke out at Morant Bay and on the 12th myself, family and B[oo]kkeepers had to fly for refuge from their violence. We returned to the estate on 20th October in HM Gunboat Nettle as far as Morant Bay and from thence on foot at which date the troops had dispersed the rebels and I at once called up the Headmen and persuaded the labourers to resume their employment. Labour is scarce…. Every item of estates supplies and house furniture has been either destroyed or stolen and the buildings generally have been much injured

The uprising was suppressed with violence by the authorities. The estate managers support this response, but they are cautious about the outcome: “although the labourers appear quiet it is hard to discover whether they have benefitted morally by the lesson taught them." (ACC/0775/950/44)

The Governor of Jamaica, Edward John Eyre, ordered extensive and harsh reprisals against suspected rebels which provoked widespread controversy both in Jamaica and in Britain. George William Gordon, a Jamaican businessman, politician, and critic of the government, was executed in the aftermath, despite there being no evidence of his direct involvement in the rebellion. His execution is referenced in a letter dated 4 January 1866:

The disposition of the labourers is anything but peaceable, more particularly since the arrival of the last packet by which accounts of much dissatisfaction regarding Mr G W Gordon’s execution has been received

Following the investigation of the rebellion and its aftermath by a Royal Commission, Eyre was removed from his post and recalled by the Colonial Office, but repeated attempts to prosecute him for sanctioning Gordon’s death were quashed by juries in Britain.

The volatility of the situation remains a concern for the estate managers who write in July 1866:

The behaviour of the people is mainly dependent on the result of the Commission of Enquiry on the Rebellion which has not yet been made known in Jamaica they now appear quite quiet

The Morant Bay Rebellion is not the only uprising which features in the records, either. Earlier papers relating to the plantations in Grenada briefly mention Fédon's Rebellion of 1795, a major uprising of enslaved people against British rule in Grenada which was inspired by the Revolution in Haiti (ACC/0775/953/18).

Conclusion

Much of this inclusive cataloguing work is complex, time consuming and resource heavy. It is also contested. We acknowledge that we won’t always get things right, but we aim to be transparent in what we do and to generate conversations about the complexities of London’s histories.

Such work is as important as it is satisfying. By promoting neglected stories and rebalancing narratives we aim to broaden the margins of history, to improve understanding, inspire participation and challenge narrow views about the past where they exclude and devalue the histories and contributions of marginalised groups.

That these papers warrant more detailed research is hopefully clear from the above snippets. We hope that the improved catalogue entries will generate wider interest in these collections and enable you to explore the content more fully.

If you see things on our catalogue which you think should be addressed by our Terminology Working Group or have comments about any of our catalogue descriptions, we’d love to hear from you: ask@tla.libanswers.com